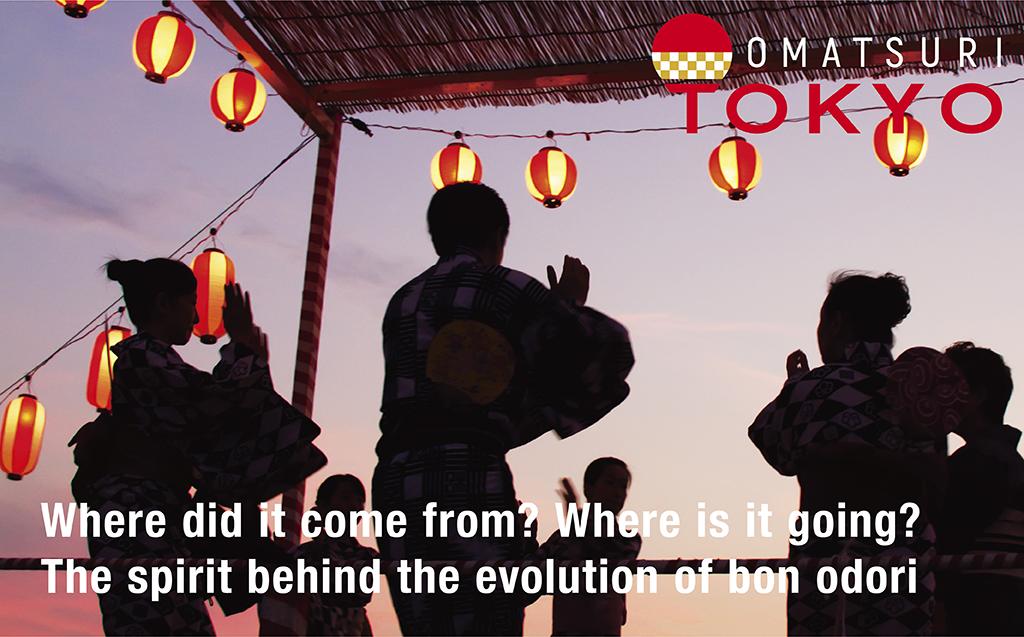

【Vol.04】Where did it come from? Where is it going? The spirit behind the evolution of bon odori

The underlying element of popularity

from odori nembutsu to “Oba-Q Ondo”

Bon odori was originally linked closely to the Buddhist ritual of honoring the spirits of the dead, called urabon-e, or obon for short. Japanese families welcome the spirits of their ancestors, dance together in their honor, and send them back again. In essence, bon odori is a religious ceremony within this orderly flow.

A starting point of this bon odori is believed to be odori nembutsu, a sacred dance made popular by Ippen, the mid-13th century monk and founder of the Ji-shu sect of Pure Land Buddhism. The idea was that dancing and reciting the nembutsu prayer promises peaceful death. Scenes of followers performing the dance unfold in the picture scroll Ippen Hijiri-e, illustrating Ippen’s travels throughout Japan. With the passage of time, the sacred ceremony of odori nembutsu acquired elements of entertainment and a performing art. It transformed into a fun event for ordinary people, and gave rise to local bon odori cultures up and down Japan.

A turning point in the evolution of bon odori was “Tokyo Ondo” (roughly, “Tokyo beat”), which became a nationwide hit soon after it was released on phonograph record in 1933. Thereafter, local numbers emerged elsewhere incorporating the place name into the title and lyrics. This led to the broad popularity of bon odori as a fun event, in addition to traditionally passed down events.

In the mid-1960s, “Oba-Q Ondo,” after the manga character Little Ghost Q-Taro, sold a whopping 2 million records, prompting bon odori to absorb the musical elements of all sorts of cultures such as anime, comics, Japanese idols, disco, and pop music. Chances are, bon odori at present is not the future Ippen envisioned when he started odori nembutsu over seven centuries ago.

Recent moves to re-evaluate bon odori

and identify its significance today

Bon odori is also a mirror of the changing times. On the one hand, many events have vanished as communities that previously sustained bon odori are being wiped out by Japan’s declining birthrate and aging population. On the other, bon odori has served as the glue that knits together residents in housing complexes, rural residential developments, and other new communities formed after the Second World War. And more bon odori events have been launched to support disaster-stricken areas in the wake of the devastating Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011. At this point, bon odori returned to its original purpose of honoring the spirits of the dead.

The past few years have seen moves to re-evaluate the allures of bon odori. While some regions are discovering a new wave of bon odori, others uphold and keep alive centuries-old festivals. The rhythm of bon odori music resonating across Japan in the summer is indeed diverse and manifold.

Text: Hajime Oishi Photographs: Keiko Oishi

(This is a "Tokyo Tokyo Old meets New" Project.)